And we’re back for the weekly writing effort. This time I’m going to post a chapter from something much larger, I hope. This is a huge gamble, as I don’t have the later stuff written, so it’s possible I end up writing myself into a corner! 😆

Just as in previous weeks I’ll have a little blurb at the end talking about where this idea came from.

Thanks for reading!

On with the show…

Six months ago, Aržak [Ar-jh-ack] was a free man, a scribe to the richest men in Ecbatana, home to the robust mints of the Parthian Empire. And then the Romans came, leveling entire cities in their wake, and enslaving everyone they could get their hands on. Something had changed. This was not the formidable, but ultimately human, Roman army of decades past. They marched with impunity. They assaulted city walls with unearthly fire. When their soldiers suffered fatal wounds, a priest would lay hands on them, and they would rise again, ready to continue the fight. What devilry had given them this power?

Aržak, like thousands of other Parthians, was now the property of Rome.

But it wasn’t cities, or even people, the Romans were after. They scoured the earth for a rare mineral, a red crystal that, to Aržak’s eyes, had no extraordinary value, other than being aesthetically pleasing. Surely Emperor Trajan wasn’t sending his armies to the edges of the world to make fine jewelry?

Aržak and his fellow captives had not been informed of where they were going, or why, nor were any explicitly aware from where they had departed, but Aržak knew. The Romans were looking for strong backs, but they had vastly misjudged Aržak’s ability to move stones, and in the process underestimated his skill with language and history.

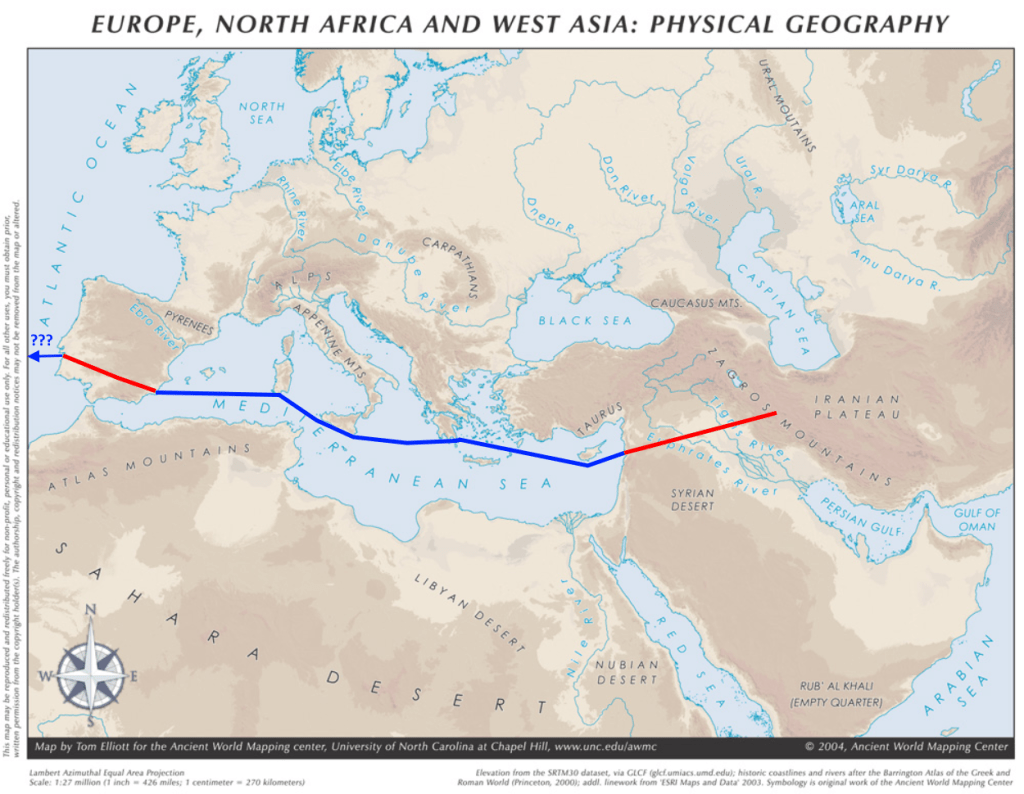

After his capture in Ecbatana, Aržak, and his fellow Parthians, had been taken west across Syria to the sea. There they were loaded on boats and sailed west, stopping in Hellas, Sicilia, Sardinia, and at last disembarking somewhere on the east coast of Hispania. They continued their march west overland, and in Corduba they were joined by thousands of men and women from all over the edges of the Roman Empire. Sarmatians, Suebians, Caledonians, and dozens of cultures and languages Aržak had never heard before. Mixed in were Roman subjects; Gauls, Aegyptians, Dacians, Britanians, even Graecians and proper Romans. Dissidents perhaps? Or simply too poor to buy their way out of some manufactured crime designed to sell them into bondage?

It was here that they were separated into groupings with few, if any, people from the same culture. Gone from Aržak’s ear were the sounds of Aramaic, Greek and the Iranian tongues, replaced by Gaulish, Germanic, and languages from beyond the deserts south of Mauretania. This, the Romans theorized, would limit cooperative efforts to escape.

They were right.

From Corduba they continued the march west, to the province of Lusitania. And it was from there they were loaded on large sailing ships and set sail across the Sea of Atlas. The ships numbered close to one hundred, and each housed one hundred slaves. What could the Romans possibly need so many workers for?

As best as Aržak could tell, they had been at sea for almost two and a half months, heading due west nearly the entire time, until the last three days, when the ship began heading north. The weather had been unnaturally favorable, with a strong tail wind, no storms, and even a light overcast the entire trip, save for at night, when the clouds cleared, allowing the navigators to more accurately judge their celestial heading. This, he surmised, may have something to do with the mysterious priests, stationed on the deck of the ship, in constant concentration and murmuring prayer. Devilry indeed.

Where could they be? Aržak was familiar with the philosophies of Eratosthenes and Posidonius. According to them, the Earth was over twenty thousand miles around. He was no sailor, but gathered from the sailors chattering, they were traveling around seventy miles per day. That would put them almost five thousand miles from where they set out. The people of Parthia had regular contact with traders from the Han, far to the East, but the Han lands were said to be only four thousand miles away from Ecbatana. Could there be land so far beyond that? Or could the philosophers have been wrong, and they found themselves on the eastern coast of the Han lands?

After the two and a half weeks, the ships turned north and sailed a further three days before reaching their final destination, an elaborate Roman port, surrounded by inhospitable marsh. It was here that Aržak caught his first glimpse of the local people. They dressed like no Han or Satavahana he had ever seen. They were naked, save for a pouch to secure their virility, with face and skin painted in elaborate patterns. They spoke in a tongue wholly unfamiliar to anything he’d heard murmured in the long weeks at sea.

For all the cruelty the Romans had inflicted upon their neighbors, and own people, they seemed amenable to these, seemingly, less sophisticated locals. Aržak could not understand them, but he could understand the Latin as one Roman translated to another. These people, the Hattacii, as the Romans called them, warned of flooding along the road and increased activity of crocodiles. And it was these Hattacii that guided the procession of slaves, as many as eight thousand that had survived the journey, along a paved road north to the end of their long odyssey.

A day’s march north and the swamps gave way to an unnaturally cloudy river and flood plain, along the upper ridge of which the Roman road ran. Long before there was any hint of what their destination might be, the land changed. The forest around had been flattened. Not hacked down by hatchet or saw, but by some great force the trees were simply knocked over, uprooted, or smashed. Finally, nearing the end of the second day’s march they came to a massive Roman fortification, with twenty foot wooden palisades, built upon earthen embankments, stretching at least a mile in either direction. And at the center of this fort was a crater a mile across and hundreds of feet deep.

The Romans were mining whatever caused the crater. Thousands of people worked with shovel and pick, with thousands more carting away the detritus up the long ramps to reinforce the fortifications. In addition, a massive pumping operation had been built, with men and beast working non-stop to move great wheels pulling ground water out and depositing it to the nearby river.

This would be Aržak’s toil for the coming months, and toil he would.

But what were they digging for? None other than the mysterious red crystal. Found only in trace fragments in Roman lands, here it was mined in vast quantities at the bottom of the crater.

Despite the Roman’s best efforts to separate slaves into unintelligible cultural groups, it didn’t take long for the slaves to find ways to communicate with one another. Men like Aržak, with his many languages already known, found themselves a hot commodity on the underground market. Even the Romans would occasionally come to him, discretely asking for his services, so that they might woo a slave, who was in no position to reject their reprehensible advances.

This clandestine duty put Aržak in the enviable position to hear all the gossip and rumors about what was going on. Around the time when Aržak’s grandparents were born, a great calamity fell upon the world. A fire raged across the sky and then the world went dark for a year. Crops failed, untold thousands starved. Every culture knew of this event and had their own tale of how and why this happened, but none of them were correct.

As Aržak would learn, thousands of miles from the world they knew, was the end result of that calamity. The fire that fell from the sky contained that red crystal, which the Roman’s coveted, claiming it held great power. It came down here in this distant place and through some mysterious workings had drawn the Romans to it.

The massive fortifications would suggest that the Romans weren’t the only ones drawn to it. But with the local people being peaceful and agreeable, who, or what, then, were the Romans afraid of?

Aržak was soon to find out.

This is my attempt to create some kind of cohesive narrative from a Dungeons and Dragons campaign I ran a few years ago. I don’t know how many specifics I’ll borrow from the events of the game, but the basic premise of the Romans having access to magic and sailing around the world to find the source of that magic remains.

It goes without saying that I’ll be removing any specific references to unique D&D concepts, as they are totally unnecessary for the story I want to tell.

I hope you enjoyed. Maybe you didn’t? That’s alright. Thanks anyway!

One thought on “Terra Magicae: Chapter 1”